Has Stephanie Ruhle Had A Stroke - Grammar Explained

Sometimes, a simple question can make us pause and think about the way we put words together. It's a funny thing, isn't it, how a few chosen words can spark a whole lot of thought about language itself? We often find ourselves curious about things, and that curiosity naturally leads us to ask questions, some of which might even touch on rather sensitive topics about public figures.

When a question like "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke" pops up, it does more than just seek information. It actually, in a way, shines a light on some interesting points about how our language works, especially when we are talking about actions that have happened or situations that exist right now. You see, the words we pick and how we arrange them can really change the entire sense of what we are trying to get across, and sometimes, it's a bit more involved than we might first think.

So, instead of focusing on the specific details of any individual's personal circumstances, which we wouldn't have any information about anyway, our conversation today is really about the mechanics of language. We are going to look closely at the sorts of grammatical choices we make when we form questions that begin with "has" or "is," or when we are trying to figure out the right way to talk about things that have happened. It's a chance to get a better grip on how we construct clear and accurate thoughts with our words, you know, just like when we ask "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke" and want to make sure we're using the right words.

- Kanyes Wife At The Grammys 2025

- Paul Mescal Looking At Daisy Edgar Jones

- Robert Pattinson And Kristen Stewart Broke Up

- Sheryl Crow Hair

- Nia Jax Bathing Suit

Table of Contents

- A Quick Note on Stephanie Ruhle's Background

- Why Do We Ask "Has" and Not "Is" When We Talk About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

- What's the Difference Between "Has Had" and "Has Been Having" When Asking About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

- Does the Way We Ask About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke" Change With Helper Words?

- Who Decides How We Talk About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

- Understanding Actions That Finished - Like "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"

- When We Say "Not" Versus "Never" About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"

- Talking About Things That Will Be Done, Even About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"

- A Quick Look Back at Our Language Chat

A Quick Note on Stephanie Ruhle's Background

When you hear a name like Stephanie Ruhle, you might naturally wonder about her background, her career journey, or perhaps even personal events. People often seek information about public figures. However, our conversation today isn't about her life story itself, but rather, it's about the very words we use when we form questions about someone, particularly when we ask something like "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke." You see, the way we structure these kinds of inquiries really matters, and it brings up some rather interesting points about how our language works, almost like a puzzle. We're here to talk about the bits and pieces of grammar that help us put such questions together properly, not to discuss personal details, which we simply don't have. It's a way of looking at the framework of our speech, so to speak.

Why Do We Ask "Has" and Not "Is" When We Talk About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

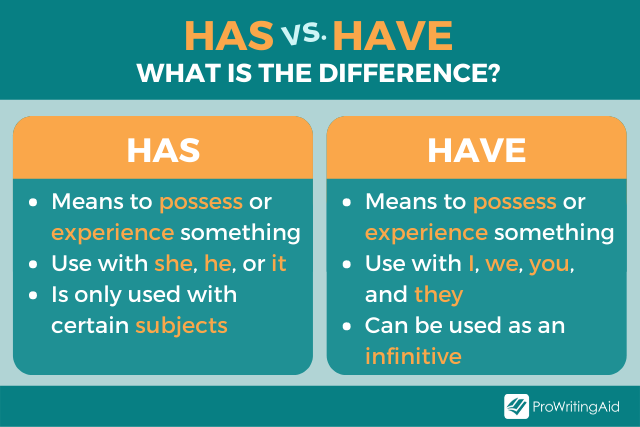

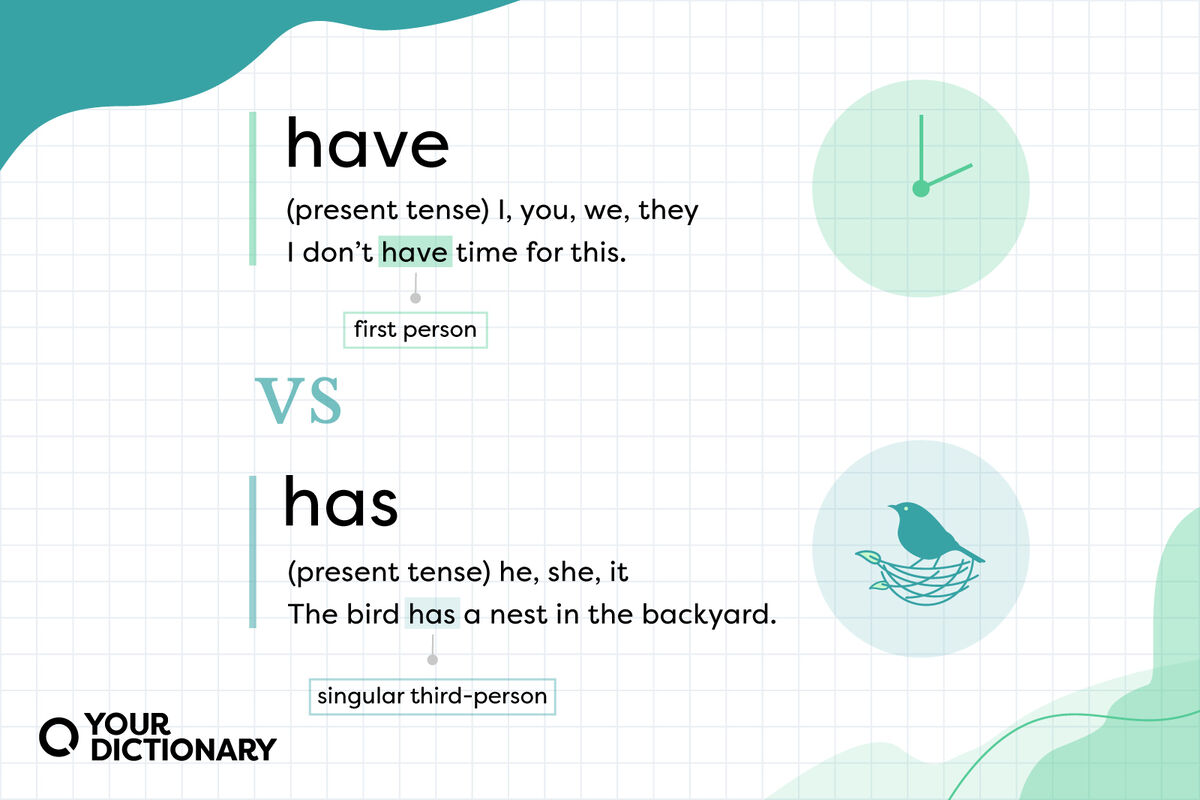

It's a common point of confusion for many: when do you use "is" and when do you use "has" when talking about something that has taken place? This is a pretty important distinction, and it comes up a lot, like when someone asks "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke." You might wonder, why not "is Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke"? Well, it's a matter of what kind of verb we are using and what we want to communicate. For example, you wouldn't typically say "Tea is come" if you mean the tea has arrived. You would say "Tea has come," because "has come" shows a completed action that has a connection to the present moment. Similarly, if someone were to return, we would say "He has come back," not "He is come back." This is because "has" acts as a helper verb here, working with a past form of another verb to show an action that is done and finished.

On the other hand, we use "is" when we are talking about a state of being or a description. For instance, you would say "Lunch is ready," because "ready" describes the state of the lunch. It's not an action that the lunch performed. So, when we ask "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke," we are using "has" because "had" is the past form of the verb "to have," indicating an experience or an event that occurred. It's about a completed action, not a description of her current state using a past participle as an adjective. It's a subtle but really important difference, and getting it right helps us speak more clearly, so it's almost like a little linguistic rule we follow.

- Rihanna And Ciara

- Is Darren Criss From Glee Married

- Utah Mom Dies After Giving Birth To Twins

- Brittany Tiffany Coffland

- Seven Andre 3000 Son

Think about it like this: if you say "The door is open," you're describing the door's current state. But if you say "The door has opened," you're talking about an action that took place and resulted in the door being open now. So, when we consider the question "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke," we are asking about an event, something that might have happened to her. We are not describing her as "stroke-had," which just sounds a bit odd, does it not? The "has" here helps us form what we call the present perfect tense, which links a past event to the present moment, perhaps because of its ongoing impact or relevance. This kind of structure is very typical for questions about completed experiences, and that, in some respects, is why it's the correct choice here.

What's the Difference Between "Has Had" and "Has Been Having" When Asking About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

This brings us to another interesting point about how verbs work: the difference between "has" and "has been," especially when we talk about something like "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke." The provided text mentions "the idea has deleted" versus "the idea has been deleted." This shows a really clear distinction between active and passive voice. When you say "the idea has deleted," it sounds like the idea itself did the deleting, which is pretty unlikely, isn't it? Ideas don't usually go around deleting things on their own. But when you say "the idea has been deleted," it means that someone or something else deleted the idea. The action was done *to* the idea, not *by* the idea. This is what we call the passive voice, and it's used when the thing receiving the action is the main focus.

Now, let's look at this in the context of our main question, "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke." Here, "had" is the past form of "to have," meaning to experience or suffer. So, "has had" is in the active voice; it means she experienced it. If we were to try to use "has been" in a similar way, like "has Stephanie Ruhle been had a stroke," it just doesn't sound right at all. That's because "has been" is usually followed by a verb ending in "-ing" (to show an ongoing action in the past that continues to the present, like "has been working") or by a past participle in the passive voice (like "has been seen"). So, if you were to ask "has Stephanie Ruhle been having a stroke," that would imply an ongoing process, a continuous event, which is a bit different from asking if a single event, a stroke, has occurred. It's a subtle distinction, but it's important for getting the right meaning across, you know, when we are trying to be very clear.

Consider these examples: "He has read the book" (active, completed action) versus "The book has been read" (passive, someone read it). Or, "She has been reading all morning" (ongoing action). When we use "has had" in "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke," we are speaking of a completed event, an experience that, if it happened, is now done. It's not something that is continuously happening. The choice of "has had" over something like "has been having" changes the entire temporal meaning of the question, making it about a singular event rather than an ongoing process. So, it's quite a precise way of expressing things, actually.

Does the Way We Ask About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke" Change With Helper Words?

The text also touches on helper words, also known as auxiliary verbs, like "do," "does," and "did." It points out that you don't use "has" with these helper words in questions or negative statements. This is a pretty common error, but once you get the hang of it, it makes perfect sense. For instance, you wouldn't ask "Does she has a child?" That just sounds a bit off, doesn't it? The correct way to ask is "Does she have a child?" The "do" or "does" takes the tense, and the main verb, "have," goes back to its basic form. This rule applies across the board, so it's a good one to keep in mind, you know, for all sorts of questions.

So, when we think about questions related to "has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke," we're usually using "has" as the primary helper verb for the present perfect tense. But what if we wanted to ask a simpler question about her health, like, "Does Stephanie Ruhle have any health concerns?" Here, because we are using "does" as our helper word for a present tense question, the verb that follows must be "have," not "has." It's a simple rule: "do," "does," and "did" always pair with the base form of the main verb, no matter the subject. This is a rather clear way to keep our questions grammatically sound and easy to understand for everyone, so it's pretty important.

This rule is quite important because it helps maintain consistency in our language. If we were to say "Did he has a good time?" it would sound very unusual to a native speaker. Instead, we say "Did he have a good time?" The "did" already tells us it's past tense, so "have" doesn't need to change. Similarly, in a negative statement, we say "She does not have a car," not "She does not has a car." This consistency helps avoid misunderstandings and makes our sentences flow much better. It's almost like a little internal rhythm that our language follows, you know, when we're putting sentences together.

Who Decides How We Talk About "has stephanie ruhle had a stroke"?

The provided text brings up an interesting point about "who agrees with the verb when who is." This is about subject-verb agreement, especially when "who" is the subject of a question. When we ask "Who has the information?" the verb "has" agrees with "who" as if "who" were a singular subject, like "he" or "she." This is generally the rule for "who" when it refers to an unspecified single person. So, if we were to ask "Who has heard about 'has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke'?" we would use "has" because "who" is treated as singular here. It's a bit like asking "Which single person has heard?"

However, if "who" is clearly referring to multiple people, the verb might change. For instance, if you were to say, "The people who have gathered here are ready," then "have" agrees with "people." But in a direct question with "who" as the subject, especially when the answer could be one person, "has" is the typical choice. It's a subtle point, but it shows how our language adapts based on what we are trying to convey, even if the subject is a bit vague. It's almost as if the language leans towards the simpler, singular interpretation unless told otherwise, you know, in some respects.

This agreement between the subject and the verb is a pretty basic building block of our language. It ensures that our sentences make sense and are grammatically sound. If the subject is singular, the verb typically takes a singular form. If the subject is plural, the verb takes a plural form. Even with words like "who," which can sometimes be tricky, the underlying principle of agreement still applies. So, when we ask questions like "Who has the answer?" or "Who has seen the latest news about 'has Stephanie Ruhle had a stroke'?", we are naturally following these established patterns of agreement

Article Recommendations

Detail Author:

- Name : Rozella Stoltenberg

- Username : agustina.dach

- Email : owolff@rippin.org

- Birthdate : 1999-08-31

- Address : 77461 Marion Motorway Boscoview, CT 38740

- Phone : 423-372-9005

- Company : Botsford-Paucek

- Job : Psychiatric Technician

- Bio : Quia blanditiis et placeat sint voluptatum ratione. Dolore sed aut beatae beatae. Est ut qui itaque sunt.

Socials

twitter:

- url : https://twitter.com/gerardo_kshlerin

- username : gerardo_kshlerin

- bio : Doloremque error dolor omnis minus. Aliquam maiores sunt consequatur qui. Eum aspernatur quas eligendi quisquam accusantium atque velit.

- followers : 542

- following : 1297

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@gerardokshlerin

- username : gerardokshlerin

- bio : Aut tempora ut blanditiis ad eligendi dicta.

- followers : 2911

- following : 771

instagram:

- url : https://instagram.com/gerardo_dev

- username : gerardo_dev

- bio : Itaque occaecati quo esse libero error. Qui molestiae reiciendis et eos molestias.

- followers : 2197

- following : 1057